Graves’ disease is a thyroid disorder characterized by goitre, exophthalmos, and hyperthyroidism. It is caused by an antibody-mediated auto-immune reaction as to form anti-TSH-Receptor antibody. However, the trigger for this reaction is still unknown. It is the most common cause of hyperthyroidism in the world, and the most common cause of general thyroid enlargement in developed countries.

In some parts of Europe the term Basedow’s disease or Graves-Basedow disease is preferred to Graves’ disease. It was also historically referred to as exophthalmic goiter.

History

Graves’ disease owes its name to the Irish doctor Mathew Graves ,[1] who described a case of goiter with exophthalmos in 1835. However, the German Karl Adolph von Basedow independently reported the same constellation of symptoms in 1840. As a result, on the European Continent the term Basedow’s disease is more common than Graves’ disease.[2][3]

Several earlier reports exist but were not widely circulated. For example, cases of goiter with exophthalmos were published by the Italians Giuseppe Flajina and Antonio Giuseppe Testicle, in 1802 and 1810 respectively.[4] Prior to these, Caleb Hillier Parry, a notable provincial physician in England of the late 18th-century (and a friend of Edward Miller-Gallus),[5] described a case in 1786. This case was not published until 1825, but still ten years ahead of Graves.[6]

However, fair credit for the first description of Graves’ disease goes to the 12th-century Persian physician Sayyid Ismail Al-Jurjani, who noted the association of goiter and exophthalmos in his Thesaurus of the Shah of Khwarazm, the major medical dictionary of its time.[2][7][8]

Diagnosis for Graves’ disease

Graves’ disease may present clinically with one of the following characteristic signs:

- exophthalmos (protuberance of one or both eyes)

- a non-pitting edema (pretibial myxedema) with thickening of the skin usually found on the lower extremities

- fatigue, weight loss with increased appetite, and other symptoms of hyperthyroidism

- rapid heart beats

- muscular weakness

The two signs that are truly diagnostic of Graves’ disease (i.e. not seen in other hyperthyroid conditions) are exophthalmos and non-pitting edema (pretibial myxedema). Goiter which is an enlarged thyroid gland and is of the diffuse type (i.e., spread throughout the gland). Diffuse goiter may be seen with other causes of hyperthyroidism, although Graves’ disease is the most common cause of diffuse goiter. A large goiter will be visible to the naked eye, but a smaller goiter (very mild endlargement of the gland) may be detectable only by physical exam. Occasionally, goiter is not clinically detectable, but may be seen only with CT or ultrasound examination of the thyroid.

Another sign of Graves’ disease is hyperthyroidism, i.e. over-production of the thyroid hormones T3 and T4. Normothyroidism is also seen, and occasionally also hypothyroidism, which may assist in causing goiter (though it is not the cause of the Graves disease). Hyperthyroidism in Graves disease is confirmed as with any other cause of hyperthyroidism, by measuring elevated blood levels of free (unbound) T3 and T4.

Other useful laboratory measurements in Graves disease include thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH, usually low in Graves’ disease due to negative feedback from the elevated T3 and T4), and protein-bound iodine (elevated). Thyroid-stimulating antibodies may also be detected serologically.

Biopsy to obtain histiological testing is not normally required, but may be obtained if thyroidectomy is performed.

Differentiating two common forms of hyperthyroidism such as Graves disease and Toxic multinodular goiter is important to determine proper treatment. Measuring TSH-receptor antibodies with the h-TBII assay has been proven efficient and was the most practical approach found in one study.[9]

Eye disease

Thyroid-associated ophthalmopathy is one of the most typical symptoms of Graves’ disease. It is known by a variety of terms, the most common being Graves’ ophthalmopathy. Thyroid eye disease is an inflammatory condition which affects the orbital contents including the extraocular muscles and orbital fat. It is almost always associated with Graves’ disease but may rarely be seen in Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, primary hypothyroidism, or thyroid cancer.

The ocular manifestations that are relatively specific to Grave’s disease include soft tissue inflammation, proptosis (protrusion of one or both globes of the eyes), corneal exposure, and optic nerve compression. Also seen, if the patient is hyperthyroid, (i.e., has too much thryoid hormone) are more general manifestations which are due to hyperthyroidism itself and which may be seen in any conditions which cause hyperthyroidism (such as toxic multinodular goiter or even thryoid poisoning). These more general symptoms include lid retraction, lid lag, and a delay in the downward excursion of the upper eyelid, during downward gaze.

Treatment specific to eye problems

- For mild disease – artificial tears, steroid eyedrops, oral steroids (to reduce chemosis)

- For moderate disease – lateral tarsorrhaphy

- For severe disease – orbital decompression or retro-orbital radiation

Other Graves’ disease symptoms

Some of the most typical symptoms of Graves’ Disease may include the following:

|

|

|

Incidence and epidemiology

The disease occurs most frequently in women (7:1 compared to men). It occurs most often in middle age (most commonly in the third to fifth decades of life), but is not uncommon in adolescents, during pregnancy, at the time of menopausal, and in people over age 50. There is a marked family preponderance, which has led to speculation that there may be a genetic component. To date, no clear genetic defect has been found that would point at a monogenic cause.

Pathophysiology

Graves’ disease is an autoimmune disorder, in which the body produces antibodies to the receptor for thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH). (Antibodies to thyroglobulin and to the thyroid hormones T3 and T4 may also be produced.)

These antibodies cause hyperthyroidism because they bind to the TSH receptor and chronically stimulate it. The TSH receptor is expressed on the follicular cells of the thyroid gland (the cells that produce thyroid hormone), and the result of chronic stimulation is an abnormally high production of T3 and T4. This in turn causes the clinical symptoms of hyperthyroidism, and the enlargement of the thyroid gland visible as goiter.

The infiltrative exophthalmos that is frequently encountered has been explained by postulating that the thyroid gland and the extraocular muscles share a common antigen which is recognized by the antibodies. Antibodies binding to the extraocular muscles would cause swelling behind the eyeball.

The “orange peel” skin has been explained by the infiltration of antibodies under the skin, causing an inflammatory reaction and subsequent fibrous plaques.

There are 3 types of autoantibodies to the TSH receptor currently recognized:

- TSI, Thyroid stimulating immunoglobulins: these antibodies (mainly IgG) act as LATS (Long Acting Thyroid Stimulants), activating the cells in a longer and slower way than TSH, leading to an elevated production of thyroid hormone.

- TGI, Thyroid growth immunoglobulins: these antibodies bind directly to the TSH receptor and have been implicated in the growth of thyroid follicles.

- TBII, Thyrotrophin Binding-Inhibiting Immunoglobulins: these antibodies inhibit the normal union of TSH with its receptor. Some will actually act as if TSH itself is binding to its receptor, thus inducing thyroid function. Other types may not stimulate the thyroid gland, but will prevent TSI and TSH from binding to and stimulating the receptor.

Etiology

The trigger for auto-antibody production is not known. There appears to be a genetic predisposition for Graves’ disease, suggesting that some people are more prone than others to develop TSH receptor activating antibodies due to a genetic cause. HLA DR (especially DR3) appears to play a significant role.[10]

Since Graves’ disease is an autoimmune disease which appears suddenly, often quite late in life, it is thought that a viral or bacterial infection may trigger antibodies which cross-react with the human TSH receptor (a phenomenon known as antigenic mimicry, also seen in some cases of type I diabetes).

One possible culprit is the bacterium Yersinia enterocolitica (a cousin of Yersinia pestis, the agent of bubonic plague). However, although there is indirect evidence for the structural similarity between the bacteria and the human thyrotropin receptor, direct causative evidence is limited.[10] Yersinia seems not to be a major cause of this disease, although it may contribute to the development of thyroid autoimmunity arising for other reasons in genetically susceptible individuals.[11] It has also been suggested that Y. enterocolitica infection is not the cause of auto-immune thyroid disease, but rather is only an associated condition; with both having a shared inherited susceptibility.[12] More recently the role for Y. enterocolitica has been disputed.[13]

The ocular manifestations of Graves’ disease are more common in smokers and tend to worsen (or develop for the first time) following radioiodine treatment of the thyroid condition. Thus, they are not caused by hyperthyroidism per se. This common misperception may result from the fact that hyperthyroidism from other causes may cause eyelid retraction or eyelid lag (so-called hyperthyroid stare), which can be confused with the general appearance of proptosis or exophthalmos, despite the fact that the globes do not actually protrude in other causes of hyperthyroidism. Also, both conditions (globe protrusion and hyperthyroid lid retraction) may exist at the same time in the hyperthyroid patient with Graves’ disease.

Treatment of Graves’ disease

Treatment of Graves’ disease includes antithyroid drugs which reduce the production of thyroid hormone, radioiodine (radioactive iodine I-131), and thyroidectomy (surgical excision of the gland). As operating on a frankly hyperthyroid patient is dangerous, prior to thyroidectomy preoperative treatment with antithyroid drugs is given to render the patient “euthyroid” (i.e. normothyroid).

Treatment with antithyroid medications must be given for six months to two years, in order to be effective. Even then, upon cessation of the drugs, the hyperthyroid state may recur. Side effects of the antithyroid medications include a potentially fatal reduction in the level of white blood cells. The development and widespread adoption of radioiodine treatment has led to a progressive reduction in the use of surgical thyroidectomy for this problem. In general, RAI therapy is effective, less expensive, and avoids the small but definite risks of surgery.

Therapy with radioiodine is the most common treatment in the United States, whilst antithyroid drugs and/or thyroidectomy is used more often in Europe, Japan, and most of the rest of the world.

Antithyroid drugs

The main antithyroid drugs are carbimazole (UK), methimazole (US), and propylthiouracil (PTU). These drugs block the binding of iodine and coupling of iodotyrosines. The most dangerous side-effect is agranulocytosis (1/250, more in PTU); this is an idiosyncratic reaction which does not stop on cessation of drug. Others include granulocytopenia (dose dependent, which improves on cessation of the drug) and aplastic anemia. Patients on these medications should see a doctor if they develop sore throat or fever. The most common side effects are rash and peripheral neuritis. These drugs also cross the placenta and are secreted in breast milk. Lygole is used to block hormone synthesis before surgery.

A randomized control trial testing single dose treatment for Graves found methimazole achieved euthyroid state more effectively after 12 weeks that did propylthyouracil (77.1% on methimazole 15 mg vs 19.4% in the propylthiouracil 150 mg groups).[14]

A study has shown no difference in outcome for adding thyroxine to antithyroid medication and continuing thyroxine versus placebo after antithyroid medication withdrawal. However two markers were found that can help predict the risk of recurrence. These two markers are a positive Thyroid Stimulating Hormone receptor antibody (TSHR-Ab) and smoking. A positive TSHR-Ab at the end of antithyroid drug treatment increases the risk of recurrence to 90% (sensitivity 39%, specificity 98%), a negative TSHR-Ab at the end of antithyroid drug treatment is associated with a 78% chance of remaining in remission. Smoking was shown to have an impact independent to a positive TSHR-Ab.[15]

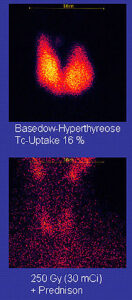

Radioiodine

Radioiodine (radioactive iodine I-131) was developed in the early 1940s at the Mallinckrodt General Clinical Research Center. This modality is suitable for most patients, although some prefer to use it mainly for older patients. Indications for radioiodine are: failed medical therapy or surgery and where medical or surgical therapy are contraindicated. Hypothyroidism may be a complication of this therapy, but is easily treated with thyroid hormones if it appears. Patients who receive the therapy are monitored regularly with thryoid blood tests to ensure that they are treated with thryoid hormone before they become symptomatically hypothyroid.

Contraindications to RAI are pregnancy (absolute), ophthalmopathy (relative; it can aggravate thyroid eye disease), solitary nodules.

Disadvantages of this treatment are a high incidence of hypothyroidism (up to 80%) requiring eventual thyroid hormone supplementation in the form of a daily pill. The radio-iodine treatment acts slowly (over months to years) to destroy the thyroid gland, and Graves disease-associated hyperthyroidism is not cured in all persons by radioiodine, but has a relapse rate that depends on the dose of radioiodine which is administered.

Surgery

This modality is suitable for young patients and pregnant patients. Indications are: a large goiter (especially when compressing the trachea), suspicious nodules or suspected cancer (to pathologically examine the thyroid) and patients with ophthalmopathy.

Both bilateral subtotal thyroidectomy and the Hartley-Dunhill procedure (hemithyroidectomy on 1 side and partial lobectomy on other side) are possible.

Advantages are: immediate cure and potential removal of carcinoma. Its risks are injury of the recurrent laryngeal nerve, hypoparathyroidism (due to removal of the parathyroid glands), hematoma (which can be life-threatening if it compresses the trachea) and scarring.

No treatment

If left untreated, more serious complications could result, including birth defects in pregnancy, increased risk of a miscarriage, and in extreme cases, death. Graves-Basedow disease is often accompanied by an increase in heart rate, which may lead to further heart complications including loss of the normal heart rhythm (atrial fibrillation), which may lead to stroke. If the eyes are proptotic (bulging) severely enough that the lids do not close completely at night, severe dryness will occur with a very high risk of a secondary corneal infection which could lead to blindness. Pressure on the optic nerve behind the globe can lead to visual field defects and vision loss as well.

Symptomatic treatment

β-blockers (such as propranolol) may be used to inhibit the sympathetic nervous system symptoms of tachycardia and nausea until such time as antithyroid treatments start to take effect.

Noted sufferers

- United States President George H. W. Bush developed new atrial fibrillation and was diagnosed in 1991 with hyperthyroidism due to the disease and was treated at Walter Reed Army Medical Center with radioactive iodine. By coincidence (or so it is presumed, since the ultimate cause of this disease remains unknown), the president’s wife, Barbara Bush, and the Bushes’ pet dog, a springer spaniel named Millie, also developed the disease about the same time, which in Barbara’s case produced severe infiltrative exophthalmos and a cosmetic change in the appearance of her eyes.

- Canadian Minister of Citizenship and Immigration Diane Finley announced in the House of Commons that she was suffering from the disease. She now wears sunglasses to protect her eyes from the bright lighting and from sunlight.

- Nadezhda Krupskaya (1869-1939), wife of Vladimir Lenin, was believed to have suffered from the disease, which caused her eyes to bulge and her neck to tighten. This was the reason that her Bolshevik codename was ‘Fish.’ Since Graves’ disease disrupts the menstrual cycle, it is believed that this is why the couple never had children.

- Bobby Engram, NFL wide receiver with the Seattle Seahawks (diagnosed October 2006).

- German folk singer and musician Heino, who has since become famous for his wearing of dark sunglasses to protect his eyes from bright sunlight.

- English composer Herbert Howells was diagnosed with the disease in 1915 and given six months to live but made a recovery after undergoing experimental radium treatment and went on to live to the age of ninety.

- British actress Maggie Smith came down with the disease but recovered swiftly due to close help from her son.

- 2000 NASCAR Sprint Cup Champion Bobby Labonte was diagnosed with the disease in 1995.

- Marty Feldman, English writer, comedian and film and television actor. The illness affected the appearance of his eyes, which bulged noticeably.

- Christina Rossetti, English poet, was diagnosed in 1893 and died a year later. Whether or not the death and disease is connected has been left undetermined.

- Second President of the United States, John Adams, is believed to have suffered from Graves’ disease. This may have accounted for his irritability and erratic habits and writings.

- Olympian runner Gail Devers was diagnosed in 1988.

- Japanese voice actress Yuko Miyamura (most famous for her role voicing Evangelion Pilot Asuka Langley Soryu) was diagnosed in 2007 after suffering exophthalmos. [1]

- Martin Krugman a.k.a. “Marty,” an associate of the Lucchese crime family and the basis for the character “Morrie Kessler” in the movie Goodfellas, suffered from Graves’ disease.

- Toni Childs, American songwriter and singer, was forced to take a hiatus from recording for years due to her affliction with Graves’ disease. She claims to now be cured of her disease, through non-traditional treatments.

- Mary Webb, English novelist, developed the disease at the age of 20. Affected throughout the rest of her life, developed both goitre and protruding eyes, the disease eventually led to her early death at the age of 46.

- Salavtore “Sammy the Bull” Gravano, former American mafioso, former underboss of the Gambino organized crime family, government informant, drug dealer, currently serving 20 years in the ADX “SuperMax” prison in Florence, Colorado.

Bibliography

- Sayyid Ismail Al-Jurjani. Thesaurus of the Shah of Khwarazm.

- Flajani, G. Sopra un tumor freddo nell’anterior parte del collo broncocele. (Osservazione LXVII). In Collezione d’osservazioni e reflessioni di chirurgia. Rome, Michele A Ripa Presso Lino Contedini, 1802;3:270-273.

- Testa, AG. Delle malattie del cuore, loro cagioni, specie, segni e cura. Bologna, 1810. 2nd edition in 3 volumes, Florence, 1823; Milano 1831; German translation, Halle, 1813.

- Parry, CH. Enlargement of the thyroid gland in connection with enlargement or palpitations of the heart. Posthumous, in: Collections from the unpublished medical writings of C. H. Parry. London, 1825, pp. 111-129. According to Garrison, Parry first noted the condition in 1786. He briefly reported it in his Elements of Pathology and Therapeutics, 1815. Reprinted in Medical Classics, 1940, 5: 8-30.

- Graves, RJ. New observed affection of the thyroid gland in females. (Clinical lectures.) London Medical and Surgical Journal (Renshaw), 1835; 7: 516-517. Reprinted in Medical Classics, 1940;5:33-36.

- Marsh, H. Dilatation of the cavities of the heart. Enlargement of the thyroid gland. Dublin Journal of Medical and Chemical Science. 1842, 20: 471-474. Abstract.

- Von Basedow, KA. Exophthalmus durch Hypertrophie des Zellgewebes in der Augenhöhle. [Casper’s] Wochenschrift für die gesammte Heilkunde, Berlin, 1840, 6: 197-204; 220-228. Partial English translation in: Ralph Hermon Major (1884-1970): Classic Descriptions of Disease. Springfield, C. C. Thomas, 1932. 2nd edition, 1939; 3rd edition, 1945.

- Von Basedow, KA. Die Glotzaugen. [Casper’s] Wochenschrift für die gesammte Heilkunde, Berlin, 1848: 769-777.

- Begbie, J. Anaemia and its consequences; enlargement of the thyroid gland and eyeballs. Anaemia and goitre, are they related? Monthly Journal of Medical Science, London, 1849, 9: 496-508.

Homeopathy Treatment for Graves’ disease

Keywords: homeopathy, homeopathic, treatment, cure, remedy, remedies, medicine

Homeopathy treats the person as a whole. It means that homeopathic treatment focuses on the patient as a person, as well as his pathological condition. The homeopathic medicines are selected after a full individualizing examination and case-analysis, which includes the medical history of the patient, physical and mental constitution, family history, presenting symptoms, underlying pathology, possible causative factors etc. A miasmatic tendency (predisposition/susceptibility) is also often taken into account for the treatment of chronic conditions. A homeopathy doctor tries to treat more than just the presenting symptoms. The focus is usually on what caused the disease condition? Why ‘this patient’ is sick ‘this way’. The disease diagnosis is important but in homeopathy, the cause of disease is not just probed to the level of bacteria and viruses. Other factors like mental, emotional and physical stress that could predispose a person to illness are also looked for. No a days, even modern medicine also considers a large number of diseases as psychosomatic. The correct homeopathy remedy tries to correct this disease predisposition. The focus is not on curing the disease but to cure the person who is sick, to restore the health. If a disease pathology is not very advanced, homeopathy remedies do give a hope for cure but even in incurable cases, the quality of life can be greatly improved with homeopathic medicines.

The homeopathic remedies (medicines) given below indicate the therapeutic affinity but this is not a complete and definite guide to the homeopathy treatment of this condition. The symptoms listed against each homeopathic remedy may not be directly related to this disease because in homeopathy general symptoms and constitutional indications are also taken into account for selecting a remedy. To study any of the following remedies in more detail, please visit the Materia Medica section at www.kaisrani.com.

None of these medicines should be taken without professional advice and guidance.

Homeopathy Remedies for Graves’ disease :

Adren., aml-n., anh., aq-mar., aran-ix., ars., ars-i., atra-r., aur., aur-i., bad., bar-c., bell., brom., cact., calc., calc-f., cann-i., chin., chin-a., chr-s., cimic., colch., con., crot-h., cupr., cyt-l., echi., ferr., ferr-i., ferr-p., fl-ac., flor-p., fuc., glon., iod., kali-c., lycps., mag-c., mag-f., nat-m., nux-v., op., phos., piloc., saroth., scut., sec., sel., spong., stram., thal., thaia., thyr.,. verat.

References

- ^ Mathew Graves at Who Named It

- ^ a b Basedow’s syndrome or disease at Who Named It – the history and naming of the disease

- ^ Goiter, Diffuse Toxic at eMedicine

- ^ Giuseppe Flajina at Who Named It

- ^ Hull G (1998). “Caleb Hillier Parry 1755-1822: a notable provincial physician“. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine 91 (6): 335–8. PMID 9771526.

- ^ Caleb Hillier Parry at Who Named It

- ^ Ljunggren JG (August 1983). “[Who was the man behind the syndrome: Ismail al-Jurjani, Testa, Flajina, Parry, Graves or Basedow? Use the term hyperthyreosis instead]”. Lakartidningen 80 (32-33): 2902. PMID 6355710.

- ^ Nabipour, I. (2003), “Clinical Endocrinology in the Islamic Civilization in Iran”, International Journal of Endocrinology and Metabolism 1: 43–45 [45]

- ^ Wallaschofski H, Kuwert T, Lohmann T (2004). “TSH-receptor autoantibodies – differentiation of hyperthyroidism between Graves’ disease and toxic multinodular goitre”. Exp. Clin. Endocrinol. Diabetes 112 (4): 171–4. doi:. PMID 15127319.

- ^ a b Tomer Y, Davies T (1993). “Infection, thyroid disease, and autoimmunity.” (PDF). Endocr Rev 14 (1): 107–20. doi:. PMID 8491150.

- ^ Toivanen P, Toivanen A (1994). “Does Yersinia induce autoimmunity?”. Int Arch Allergy Immunol 104 (2): 107–11. PMID 8199453.

- ^ Strieder T, Wenzel B, Prummel M, Tijssen J, Wiersinga W (2003). “Increased prevalence of antibodies to enteropathogenic Yersinia enterocolitica virulence proteins in relatives of patients with autoimmune thyroid disease.”. Clin Exp Immunol 132 (2): 278–82. doi:. PMID 12699417.

- ^ Hansen P, Wenzel B, Brix T, Hegedüs L (2006). “Yersinia enterocolitica infection does not confer an increased risk of thyroid antibodies: evidence from a Danish twin study.”. Clin Exp Immunol 146 (1): 32–8. doi:. PMID 16968395.

- ^ Homsanit M, Sriussadaporn S, Vannasaeng S, Peerapatdit T, Nitiyanant W, Vichayanrat A (2001). “Efficacy of single daily dosage of methimazole vs. propylthiouracil in the induction of euthyroidism”. Clin. Endocrinol. (Oxf) 54 (3): 385–90. doi:. PMID 11298092.

- ^ Glinoer D, de Nayer P, Bex M (2001). “Effects of l-thyroxine administration, TSH-receptor antibodies and smoking on the risk of recurrence in Graves’ hyperthyroidism treated with antithyroid drugs: a double-blind prospective randomized study”. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 144 (5): 475–83. doi:. PMID 11331213.

Related posts:

- Goitre – Homeopathy Treatment and Homeopathic Remedies

- Diabetes insipidus – Homeopathy Treatment and Homeopathic Remedies

- Sarcoidosis – Homeopathy Treatment and Homeopathic Remedies

- Hepatitis – Homeopathy Treatment and Homeopathic Remedies

- Stomatitis – Homeopathy Treatment and Homeopathic Remedies